Even in a world where one feels mostly accepted, we can at times feel alone and excluded—removed from others whose lives we perceive as more whole, more fulfilling, better. More difficult to accept are the ways we do the excluding, the way the other becomes stained with our unwanted parts.

I remember vividly one such moment: I had just given birth to our second daughter. My husband and I were watching the news, and there was a report on a nearby tragedy: A couple, both doctors, had lost their two young children when the ice broke while they were skating. Hearing this story, I was gripped by the horror of losing both children: This could be us. In that moment, the unimaginable was imagined. Then a photo of that beautiful, intact family appeared on the screen, taken months earlier, and I was relieved. Their skin was darker than mine. We were safe: This could not happen to us.

By erecting a barrier (us–them), I had magically separated myself from the possibility of this tragedy. Freud referred to this maneuver as the “narcissism of minor differences.” While Freud understood it as a need to project one’s aggressive impulses onto an enemy (them), I saw my reaction as self-preserving, which allowed me to feel detached, and thereby protected.

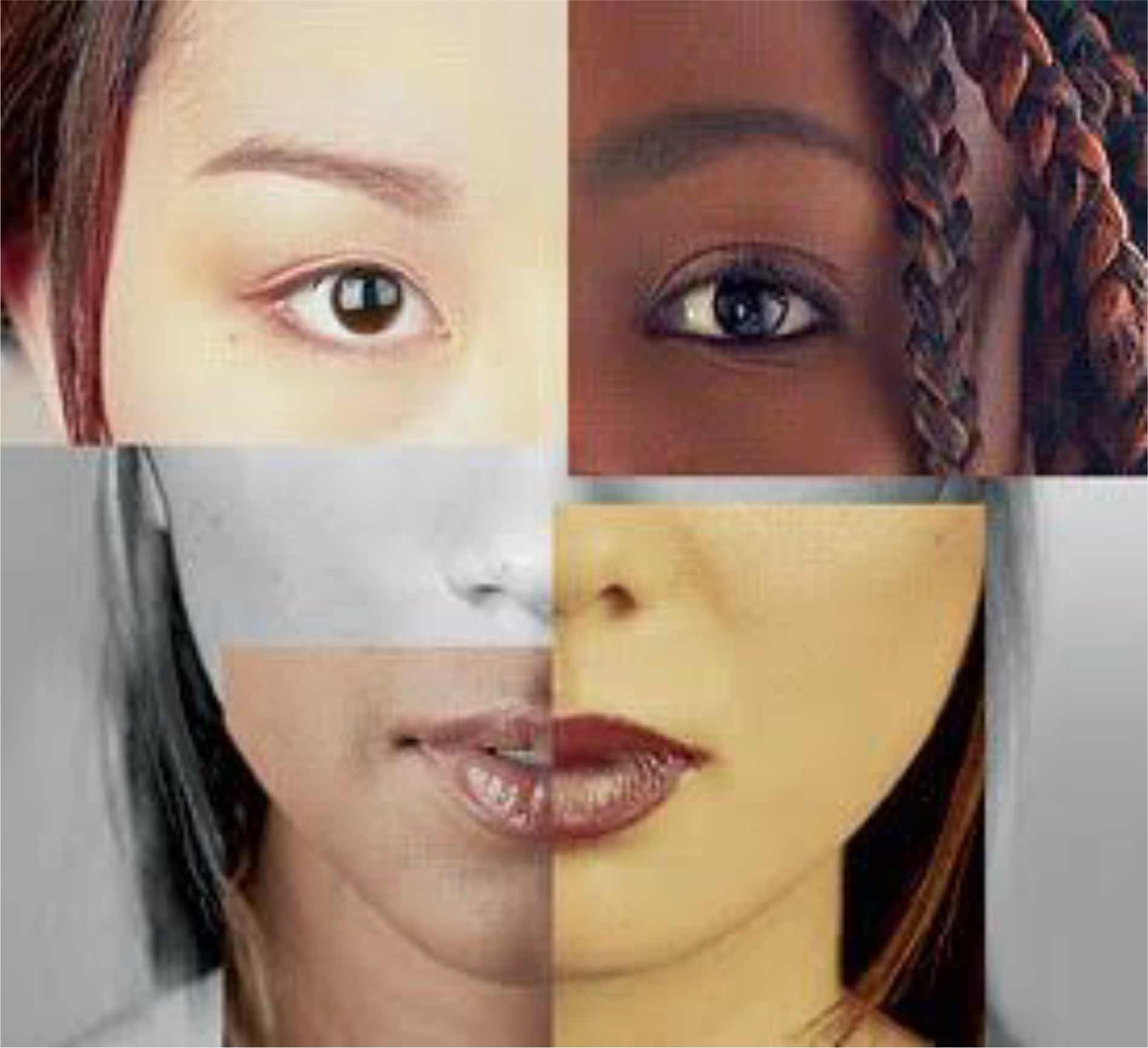

Although humans are more the same than different, we continue to focus on what distinguishes us. Daily we see the horrors committed because of minor differences: racism, violence, genocide. The myth of the other is perpetuated when we forge no connection, offer no empathy, and don’t take the time to imagine who that other is.

Each of us knows outsiderness. Those wounds should inform and preclude the ways we inflict those same wounds onto others. In these polarizing times, we must work to hold the other in mind.