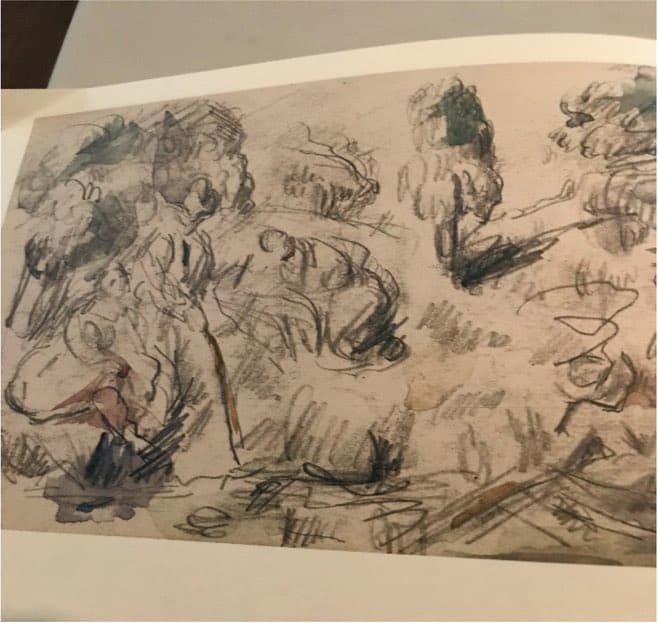

Cezanne asserted, “There is no line…a bloodless contour should not be trusted.”

All of us, we love to tell, to repeat our stories, our memories … does it do us good?

At the current Cezanne exhibit at MOMA in New York, a small placard next to the drawing “At the Edge of the Pond” reads,

This drawing of a bather reveals Cezanne’s own approach: a line that multiplies, repeats, twists, trembles and searches, Cezanne’s line creates multiple possibilities for the figure…

The American composer Nico Muhly wrote: “Philip’s (Glass) music uses repetition, but there’s a lot of drama to be found in the deviation…It’s that weird thing of a slight ecstatic disruption.”

Federico Garcia Lorca wrote “at five in the afternoon”; 28 of 52 lines contain this phrase in his poem of anguish and grief written in response to the exact moment of loss for his intimate friend, a bullfighter, “Lament for Ignacio Sanchez Mejias.” Is this repetition or rather an incantation?

Psychoanalytic psychotherapists listen again and again and find life and resonance in sameness. Freud wrote about a WWI soldier and his need to repeat his war trauma in dreaming—this story is only one paragraph removed from the story of Freud’s grandson’s repetition in the playing of “da-fort” *— horrible blinding trauma and violence only inches away (in the printed word) from a child’s need to contend with the “trauma” of a mother’s temporary absence.

The potential found in repetition is under-estimated and under-valued—too easily gathered inside the umbrella called “repetition compulsion,” conceived as pathological. Perhaps in all repetition there lies a kernel of “trauma” bending toward relief, resolution or at least the opening of an impasse.

*da/fort: This 18-month-old boy threw a wooden reel over the edge of his cot, pulling it back by the attached string repeating da (gone) and fort (there/back again). In this playful, creative manner a child is able to “master” or at least cope with his mother’s coming and going, over which he has no control.